by Torbjörn Hamnmark

In the film Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, there is a striking idea: the half hour before midnight belongs to good forces, the half hour after to evil. It is a metaphor for the forces shaping our destiny and the lesson is clear: if we want to shift the course of events, we must be prepared to use every means available.

Setting the scene

150 years ago, we embarked on the last great energy transition. Oil, long used in various forms, began to take centre stage. The first refinery opened in Romania in 1856; the first major oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania in 1859 (which actually is in the US in spite of its Transylvania inspired name) and then came Texas in 1901. What followed was a surge in global access to cheap energy, with oil becoming the fuel of economic expansion. This period, often referred to as The Great Acceleration or the Anthropocene, brought with it dramatic gains in productivity, food production, and what we consider high living standards.

But it was – and remains – an unsustainable trajectory.

That is why the 2015 Paris Agreement, under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), committed the world to net-zero emissions. The challenge is that we still do not know how to achieve it. In fact, we do not even know if it is an optimal target, and meanwhile, energy consumption keeps rising.

Have We Even Begun?

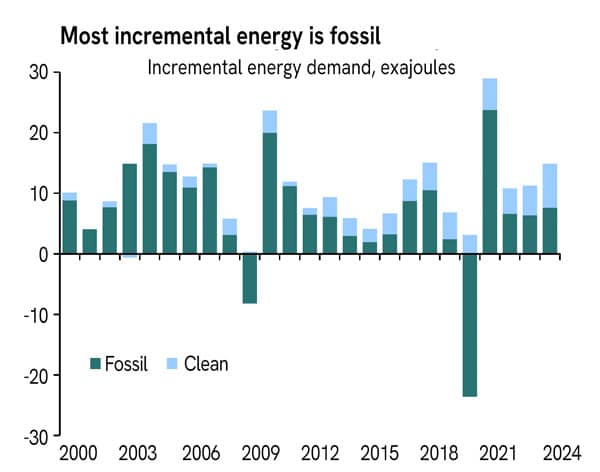

Global energy demand continues to increase, driven by rising living standards – a logical correlation. Yes, energy efficiency is improving. In wealthier economies, energy use per capita and per unit of GDP has been decreasing. That should be a reason for optimism: we can decouple prosperity from energy consumption. But here is the bad news: the vast majority of global energy demand is still met by carbon-based fuels. In other words, we have not even started the transition – yet.

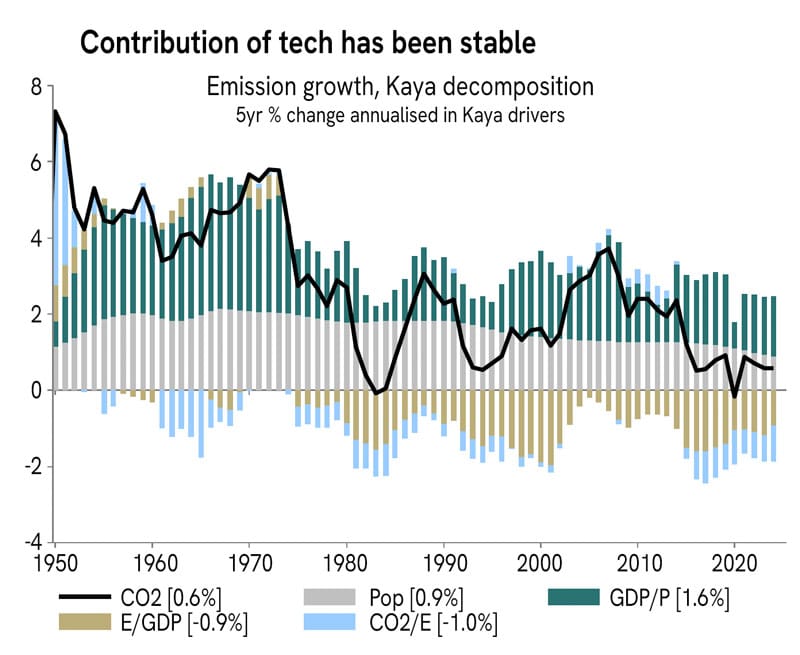

One helpful way to understand the mechanics of energy use and emissions is the Kaya Identity, which breaks down CO₂ emissions into four key factors: population, income per capita, energy intensity of income, and carbon intensity of energy. It is a simplified, yet powerful model, which explains the drivers behind the continued increase in global emissions as highlighted by this chart from Absolute Strategy Research.

What Are the Conditions for Transition Today?

Let us take a closer look. Population growth is slowing rapidly across all continents. By some estimates, global population may peak shortly after 2050. That is a powerful tailwind for a potential deceleration of emission growth.

However, per capita income continues to grow in real terms and with it, energy demand. That said, technology is helping us produce higher living standards with lower energy input per dollar and critically, we are gradually improving our ability to generate energy with less carbon intensity.

The net result? CO₂ emissions are rising at a slower rate — but the foundational relationship between economic growth and carbon-based energy use remains intact. We have not broken the dependency.

So What Will It Take?

So far, it is largely business as usual for the global energy system. Europe deserves some credit: we have made more progress here than elsewhere, and at least we have a plan.

What has worked so far? Europe again offers lessons. Since the 1970s, countries like Sweden have employed energy taxes equivalent to carbon pricing. We have shifted taxes from dirty to cleaner energy. As a result, European energy prices are 2–4x higher than in the US — and the average European uses less than half the energy of the average American.

Price signals, it turns out, do work. They become part of the invisible hand. They encourage innovation. They reward cleaner alternatives. Over the short-term, this constitutes a major “productivity handicap” but we are not in it for the short term.

However, the momentum in Europe appears to be slowing. We have difficulties keeping our eyes on the prize when pandemics, populism and productivity arguments kick in. The greatest vulnerability to our decarbonisation strategy is Europe’s inability to foresee that those countervailing forces will recur. There will inevitably be something unexpected and urgent appearing on our doorsteps to distracts us from our long-term goal.

So how can Europe withstand the dependency on Chinese supplies, become more competitive and remain a relevant global power? The Draghi report points to some good advice on strengthening the internal workings of the single market, primarily regarding financial and IT services. This makes a lot of sense. This will reduce dependency on the US and make us more competitive. These sectors alone also explain the majority of “US outperformance” (the other parts being still ongoing hyperbolic US pandemic-ignited spending –– and that Americans work 25% more hours than us Europeans). In most qualitative aspects of a modern society, Europe now appears to be increasing its lead on the US.

The China angle is tricky. I believe we should collaborate where it makes sense, not least for geopolitical reasons such as better access to resources. Europe’s population is effectively shrinking and all major global regions will compete for resources. Human resources at home will be in short supply and material resource sovereignty will take decades to achieve.

How do we convince the rest of the world to go green? Most likely by not trying. Since the global financial crisis, the US system has been regarded as “not wanted” by the Chinese while China has built its climate policies on the European model.

I believe Europe should “panic harder” when it comes to the energy transition. That will make us even more of a role model and force us to build the energy system of the future. Energy is arguably the most valuable material input to human progress. At the same time, irresponsible energy use is the most destructive force on earth. By raising the cost of irresponsible energy conversion, we can continue to build that future – is that not the real competitive edge?

A Final Thought

Energy policy remains mired in ideology. The debate is less about careful analysis and strategic planning and more about which levers — or “forces” — we consider good or evil.

If we are serious about achieving a true energy transition, we need to mobilise every tool we have ,both the good and the uncomfortable. Carbon taxes, subsidies, bans, incentives, mandates, behavioural nudges , all should be on the table.

Until then, settle in, and rewatch Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997) with John Cusack and Kevin Spacey. It is a perfect summer-night entertainment and a timely reminder that when the clock strikes midnight, make sure you have both good and evil forces on your side.

About the author

Torbjörn Hamnmark is a seasoned investment professional and finance strategist. He served as the Head of Strategic Asset Allocation at Sweden’s Third National Pension Fund (AP 3) until 2024. Previously, he led the Fixed Income division at DnB NOR Asset Management in Stockholm for a decade, and began his finance career as an options specialist at Arbitech before moving into international roles with Citibank in Frankfurt and London in the mid‑1990s- He holds an MBA in Finance & International Business and an Executive MBA in Leading Innovation from the Stockholm School of Economics. He now contributes his expertise to investment committees at Mistra and WWF Sweden where he is also serving as a board director.

Renowned for his analytical rigor, Hamnmark emphasises long‑term trends, sustainability, and scenario‑based risk management.

Graphics courtesy of Absolute Strategy Research. Reproduced with permission. Originally published on 11 July 2025 in “Climate Macro Strategy – Energy Transition: Myths & Realities”